As a member of the generation before email and ‘texting,’ and one who has always been an avid letter writer, there are many memories of trips to the local Post Office to buy stamps and personally drop the letter in the friendly red post box. The process was more complicated when mailing a letter to someone who was not in India. This meant taking a decision on whether the post should be sent by surface mail or air mail. Air mail was more expensive, albeit faster. There were two options for the air mail—the standard pre-stamped aerogramme, and the challenge to squeeze in as much text as possible in the available space, and an envelope which could accommodate more sheets and hence more matter. But then there was the issue of weight. The envelope would be weighed and the postage decided depending on the weight! Hence an earlier exercise involved acquiring the lightest, thinnest writing paper. (There was an ‘onion skin’ paper as I recall which was in itself more expensive!) Ah, the sweet travails of written communication then!

One always associated the entire concept of ‘air mail’ as having its origin in the West. Many decades later, I discovered that the very first air mail delivery happened in India!

The story goes back over a century ago. India was still under British rule but Indian festivals and fairs went on. One of the biggest of these was the Kumbh Mela held at Allahabad. It was to coincide with the Kumbh Mela of 1910-1911 that the then Lieutenant Governor of the United Provinces Sir John Prescott Hewett organized a national exhibition in Allahabad. It was a huge show housed in buildings with elaborate architecture. The twelve sections included exhibits for engineering as well as agricultural sciences, textiles, forestry, and display of handicrafts from around the world. There were cultural programmes featuring prominent singers and dancers of the day. The exhibition ran from December 1910 to February 1911.

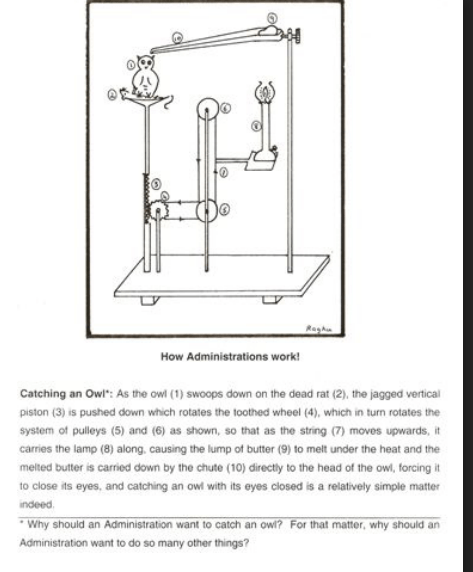

As part of the many attractions, Captain Walter George Windham, one of the influential pioneers of aviation was invited to bring some flying machines from England to Allahabad and organize demonstration flights. These would be the first planes to fly in India. Captain Windham brought two aircraft to Allahabad and organized aerial demonstrations by the two pilots that accompanied the aircraft. One of these was a 23- year-old French pilot Henri Pequet.

When Captain Windham was in Allahabad, the Rev. Holland, warden of a hostel for Indian students in Allahabad asked him if he could help raise some funds for repair of the hostel and construction of a new one. Windham had the idea that sending post by air would attract a lot of attention, and hopefully raise funds. He obtained permission from the India Post Office. To send through this, at the time novel means, people were asked to send mail to Rev. Holland, addressed and stamped, at the regular rate, but requested to donate a nominal sum of 6 annas for every letter or card which would be sent on the flight, as a donation for the new buildings. This mail would be part of the airborne postal service. A special postmark was authorised for this batch; it was designed by Captain Windham and the die for this was cast at the postal workshop in Allahabad. It was four cm in diameter and magenta in colour. All postal arrangements were handled by the Exhibition Camp Post Office.

On 18 February 1911, a Humber-Sommers bi-plane, piloted by Henri Pequet was loaded with 6,500 postal articles with the special postmark. The flight took off from the Allahabad polo field, witnessed by thousands of spectators. It landed near Naini railway station where there were no crowds, but a lone postal official who took the mail bags. From there, the post would continue to its destinations by the regular route, and with the regular charges. The distance covered was approximately 11 km and the flight time was 13 minutes! Having delivered the first officially sanctioned airborne postal consignment in the world, Peqeut got back into the plane and returned to Allahabad.

The use of a plane for delivering letters received world-wide attention once the letters with the special post mark reached England.

Before this, some transport of post by ‘air’ was not entirely unknown. During the 1800s balloons and gliders carried some mail. The first sustained powered flight by the Wright brothers on 17 December 1903 did not carry any mail, but in the decade that followed, pioneering pilots would carry ‘unofficial’ mail on their short flights. This did not have official postal authorization. The Allahabad to Naini flight carried the first ‘official’ air mail. Following this, the world’s first scheduled airmail post service took place in the UK between the London suburb of Hendon and the Postmaster General’s office in Berkshire on 9 September 1911, as part of celebrations for King George V’s coronation.

Subsequently, while the rest of the world saw rapid developments in postal air services, there was not so much happening in India. The first regular air service between India and UK was opened in 1929. Soon after that the first domestic route was opened between Karachi and Delhi. The Indian State Air Service as it was designated, ran for just two years during which it completed 197 scheduled flights, and carried 6,300 kg of mails. After its closure, the Delhi Flying Club was given permission to operate an exclusive mail service between Delhi and Karachi. Its one light aircraft carried over 7000 kg of mail during its operational period of 18 months. The big leap came in October 1932 when JRD Tata flew a Puss Moth airplane from Karachi to Bombay. The inaugural flight of India’s first air service was to become Tata Sons Ltd, and later grow into Air India, carried a load of mail. Karachi was chosen as the starting point because Imperial Airways terminated there with the mail from England, and the mail route chosen by Tatas was Karachi-Bombay-Madras (via Ahmedabad and Bellary). At the beginning the airplanes used were so small that the service was restricted to mail, but a single passenger was occasionally allowed to sit on top of the mail bags — usually with his heels higher than his head! Meanwhile the mail load had increased from about 10,500 kg in 1933 to about 30,000 kg in 1935. Larger aircraft were introduced only in 1936. While the government refused to subsidize the service, it could be sustained by a ten-year mail contact with the Government for transport of mails.

After Independence there was need for delivery of mail that was faster than through road and rail services. Daytime flights could carry only passengers. In 1949, Night Air Mail was introduced in which mail from Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay and Madras was collected at designated points in each city, delivered straight to the airport and flown to Nagpur, where it was sorted and flown back to the respective cities the same night, and delivered the next day. In the sixties there were as many as ten flights carrying mail to Nagpur in a single night. The service was discontinued in 1973. Subsequently the Indian Postal Service introduced many services including Speed Post. Today couriers and electronic exchange of information have overshadowed the work of the postal service. The postman, once eagerly awaited, and letters, eagerly opened and read and reread, have almost faded from memory. But it is important not to forget the pioneering efforts that brought us here.

–Mamata